by McKenna O’Hare

During my time in school, I took a course called Meditation and Drawing. The idea was a bit foreign to me and even somewhat frightening. I had come to understand meditation as this weird new age practice of emptying one’s mind, and this passage from Luke 11 always came to mind where an evil spirit leaves a person, returns to find “the house” clean and orderly, and therefore, invites seven more evil spirits to join, leaving the person worse off than before. As a newer believer at the time, this made me especially skeptical.

Afraid of what might happen if I achieved this mental clarity/cleansing that meditation seemed designed for, I prayed. I prayed through our guided meditations, and I prayed while drawing. I always had an ongoing stream of internal thoughts flowing because if I allowed my mind to be blank, swept and put in order, I obviously was doomed for destruction. However, what I failed to recognize at the time was that my fear of emptiness negated the reality of the Holy Spirit already dwelling within me. An unclean spirit couldn’t return to its house along with others because it no longer has ownership of the house. As Christians, we house the Holy Spirit; He is who we’ll find at the door.

Amid detangling that revelation, I now had to frame a final project around a personal practice of meditation with the guidance of any resource of choice. With the creative freedom at hand and the lingering caution I felt in regards to meditation, I sought to find a biblically sound, prayerful meditation guide. In my digging, I came across Prayer: 40 Days of Practice by Justin McRoberts and Scott Erickson. This small, devotional-like book consisted of short, guided prayers and meditations partnered with contemplative imagery, and a few suggested practices; that’s it, but it changed my prayer life in such a simple, yet radical way. Justin McRoberts offers profound grace filled one liners, while Scott Erickson invites deep contemplation, an “excavation of the soul” if you will, through his corresponding visual work.

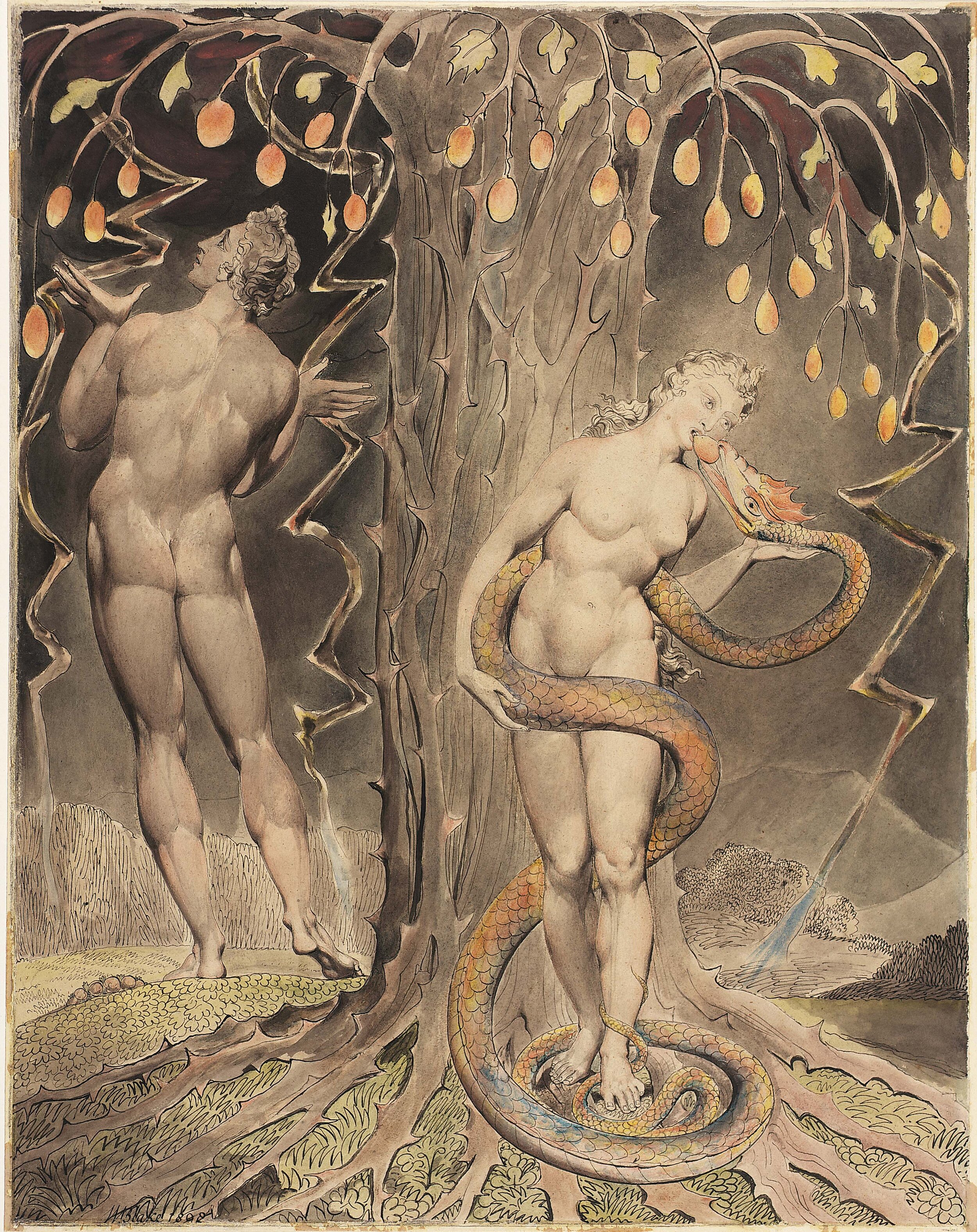

Illustration by Scott Erickson and prayer by Justin McRoberts

Within the first pages of the book’s introduction, the reader is encouraged to respond, meditate, excavate, and contemplate. I had been given permission to meditate as a Christian. This immediately shifted my understanding of meditation. It didn’t have to include gongs, mundra hand positions, and hums. It could simply be a practice of focusing, thinking deeply, and reflecting on our own lives, the lives of those around us, and the presence of God in, through and surrounding it all. Stillness isn’t something to be feared, but instead pursued, for it allows God space to be. In this way, meditation can be an avenue to commune with God himself—a form of prayer.

So, I am now invited also into unfamiliar territory of prayer. If meditation and contemplating good art can be ways to pray, what else could be? This stirred in me a sense of both curiosity and freedom. We have the ability to train our mind and hearts to the inclination of God in everything we do. This is a simple concept, but a hard thing to implement. However, this idea reoriented what I had previously thought prayer to be. Prayer became more than mere conversation, but rich communion—a practice of abiding and cultivating fellowship with God. We can filter life through the lens of prayer with a heightened awareness of the Lord’s presence among us. In doing so, nearly anything can be prayerful.

Where people once had to travel, sacrifice, and cleanse to access God, we have immediate access to the Father through the Holy Spirit because of the cross of Christ Jesus. God is closer to us than we could imagine; the commute exists within us. Thus, communion is readily available whether it be by means of bowed heads and folded hands or thoughtful words and brilliant images. Ultimately, prayer is less about the mechanics and more about the essence. God is not bound to our human traditions and limitations. He is not put off by our contemplation or even our silence; I have come to understand that He just might even delight in it.

McKenna O’Hare is a contemporary mixed-media visual artist. Her work explores connections within oneself and between others, our surroundings, and the Divine. Working from intuition and using non-objective expression, her work results in final pieces that engage the viewer and provoke contemplation.

Upon graduating with her BFA from Fort Hays State University in Hays, KS, she moved to Louisville, KY, where she currently interns at Sojourn Arts. You can view McKenna’s work at www.mckennaohare.weebly.com and by following her on Instagram @mckennaohare.

This post is part of an ongoing series where we ask artists and arts professionals to share a piece of artwork that has significantly impacted their formation as a Christian.